This post is published with permission from Amplify, the Core Knowledge Foundation’s publishing partner for the Core Knowledge Language Arts® program. This post, subtitled “How two Wisconsin researchers discovered that the comprehension gap is a knowledge gap,” examines an experiment that yielded interesting, and perhaps unexpected, results.

In Norway, Wisconsin, as in much of the state, cold winters are a way of life. People allow extra time to bundle up and then waddle through town like Michelin men edged with fur. For the few months that grass is visible, it is tightly shorn. Lake Michigan, 20 miles to the east, makes the climate a little milder, so that the first freeze comes with the end of the baseball season, and the last freeze with the start of the next. Houses appear recently painted, and the low-slung school buildings sprawl as if the architect was unsure how to fill such a generous plot of land.

In one of those buildings in 1987, two young researchers from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie, ran an experiment elegant in its simplicity but profound in its implications. They took over an empty classroom and created an 18 by 20-inch replica of a baseball field furnished with four-inch wooden figures. Over several days, they invited 64 students to enter the room one by one. Leslie silently handed each student the same story narrating half an inning of a made-up baseball game. They were asked to read the story and use the model to reenact the action. The passage began in the middle of the action:

Churniak swings and hits a slow bouncing ball toward the shortstop. Haley comes in, fields it, and throws to first, but too late. Churniak is on first with a single, Johnson stayed on third. The next batter is Whitcomb, the Cougars’ left-fielder.

All day long, Recht, dark-haired and ruddy, took copious notes, while Leslie, fair with eyes that expect you to try your best, ran through the task with a student. One 12 year old after another studied the passage and acted out the play:

The ball is returned to Claresen. He gets the sign and winds up, and throws a slider that Whitcomb hits between Manfred and Roberts for a hit.

Each student read carefully, laboring over every line, straining to capture each detail of the action.

Dulaney comes in and picks up the ball. Johnson has scored, and Churniak is heading for third. Here comes the throw and Churniak is out. Churniak argues but to no avail.

Every day, four-inch figures were pushed and pulled across the field, each motion representing the turning of the wheels in students’ brains as they worked through the play. Eventually, Recht gave each student a quiz designed to assess his or her baseball knowledge, while Leslie reset the pieces and ushered in the next kid.

It took two full weeks to work through the 64 students and another month to compile their scores and analyze the results before they were able to pinpoint who did best at correctly reconstructing the story. Was it:

- Strong readers;

- Kids with good knowledge of baseball;

- It made no difference?

Pause for a moment to make your prediction before reading further.

To their surprise, Recht and Leslie found that reading ability had little impact on how well kids understood the story. But knowledge of baseball did. In fact, those who were weaker readers did as well as strong readers if they had knowledge of baseball.

“Prior knowledge creates a scaffolding for information,” explains Recht. “For poor readers, the scaffolding allows them to compensate for their generally inefficient recognition of important ideas.”* If those same kids were taking a state test, the SAT or any other standard test of comprehension, and the passage just happened to be about baseball, they would outperform everyone else. But if they encountered a passage on a topic they knew little about, they would fare much worse.

High-stakes tests don’t contain passages on baseball precisely because that would be unfair to kids who don’t follow the sport. But they do contain passages on the founding documents of the United States, animal ecology, and space exploration. (In [another article in this issue](/blog/article/the-10-knowledge-domains-that-will-give-your-students-an-advantage-on-parcc), we present analysis of over 100 PARCC and SBAC passages, showing the prior knowledge that would give students an advantage.) Beyond test taking, others have identified the prior knowledge necessary to succeed in college and life. Beyond school, writers of newspaper articles, magazine pieces and books all make assumptions about basic knowledge shared by readers.

What Recht and Leslie showed was that knowledge counts much more than we think in understanding text. They point out that an emphasis on teaching reading strategies—such as finding the main idea and summarization—has become very prevalent in US classrooms based on evidence that they help weak readers. But practicing these strategies over and over has diminishing returns—and comes at the cost of a crucial missed opportunity; building knowledge is at least as important.

It is hard to find the “main idea” of a piece of writing if you aren’t really understanding any of the ideas. Is a kangaroo rat large like a kangaroo or small like a rat? How does a rainforest feel when you are wearing a wool uniform like the English schoolboys did in Lord of the Flies? Prior knowledge can transform a poor reader into a capable one and a poor writer into a fascinating one.

*Recht and Leslie published their research in Recht, D.R. and Leslie, L., 1988. Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), p.16.

EDH: The aha moment came back in 1978, when I realized that the community college students we were testing along with University of Virginia students could read just as well as anyone else when the topic was familiar — “Why I don’t like my roommate,” etc. But their reading began to fall off drastically in passages about the Civil War, which they were not on familiar terms with. And this was in Richmond, Virginia. In boring down into the psycholinguistic research, I found that topic familiarity was the single most important variable in reading comprehension. This meant that the most important variable for general reading ability was general knowledge. There’s no such thing as abstract “reading skill.” It’s very “domain specific,” like most skills.

EDH: The aha moment came back in 1978, when I realized that the community college students we were testing along with University of Virginia students could read just as well as anyone else when the topic was familiar — “Why I don’t like my roommate,” etc. But their reading began to fall off drastically in passages about the Civil War, which they were not on familiar terms with. And this was in Richmond, Virginia. In boring down into the psycholinguistic research, I found that topic familiarity was the single most important variable in reading comprehension. This meant that the most important variable for general reading ability was general knowledge. There’s no such thing as abstract “reading skill.” It’s very “domain specific,” like most skills. The introduction of this faster means of communication engaged the students in asking and exploring many questions: Who invented the telegraph? How did it work? What is the difference between a telegraph and a telephone? What is Morse Code? Again, these were seven-year-old students from a socio-economically and ethnically diverse community!

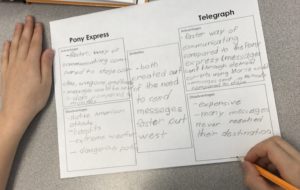

The introduction of this faster means of communication engaged the students in asking and exploring many questions: Who invented the telegraph? How did it work? What is the difference between a telegraph and a telephone? What is Morse Code? Again, these were seven-year-old students from a socio-economically and ethnically diverse community!