It’s official—summer is finally here! This is a great time for Core Knowledge teachers to discover some new books . . . beginning with some classics that may be new to you. You might start by looking at the book titles listed in the Language Arts section of each grade level of the Core Knowledge Sequence.

Are you a primary-grade-level teacher who is familiar only with your own grade level of Core Knowledge recommended titles? Check out some of the titles in the later grades, such as King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, or The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Or, are you perhaps an upper-grade teacher who has never read the many wonderful titles we recommend in the early grades, such as The Velveteen Rabbit, Charlotte’s Web, The Wind in the Willows, or even Miss Rumphius, a recommended preschool title? Do not underestimate the powerful insights and wisdom imparted in these early childhood selections just because they are intended for younger children.

It’s also a great time to explore the wide range of voices and perspectives in works by contemporary authors. Where to begin? You might start with recent Newberry and Caldecott winners, or peruse the titles selected by the Association for Library Service to Children as this year’s Notable Children’s Books.

Here at the Core Knowledge Foundation, we’d like to share the titles that we have been reading recently. Let us know what you think, and please share any book titles, using “Reply,” that you would like to recommend to Core Knowledge teachers.

Primary K-3 Picture Books for Read-Alouds

Each Kindness by Jacqueline Woodson: Chloe and her friends refuse the overtures of Maya, a new girl in their classroom. One day, when Maya is not in school, Chloe’s teacher conducts a simple lesson on kindness. Chloe realizes, sadly, that she has lost an opportunity to show kindness to Maya, who has moved away with her family.

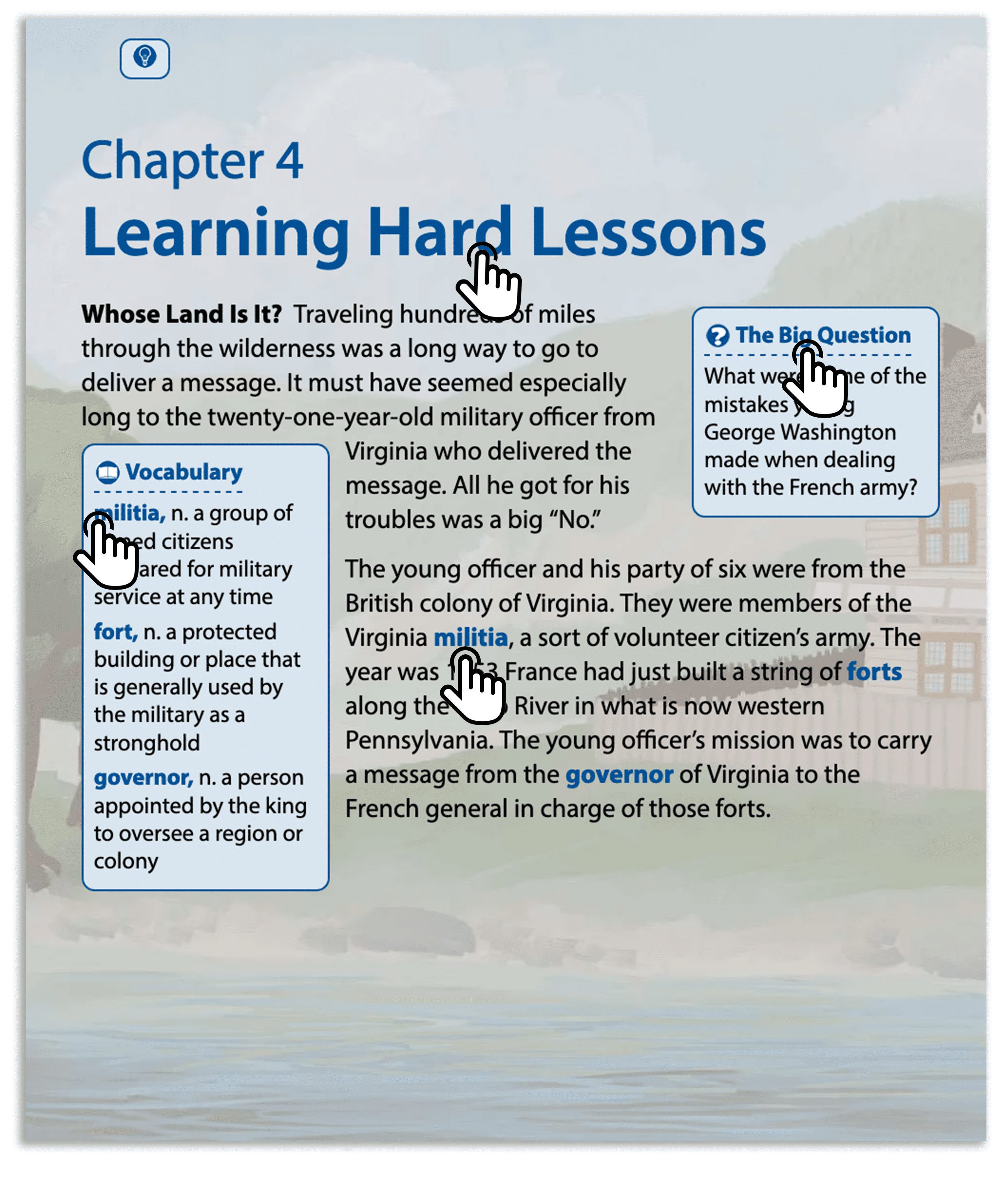

George by Frank Keating: In this first-person narration, Revolutionary War hero George Washington recounts the key facts of his life, from birth to his election as president of the new United States. The book interweaves Washington’s account with quotes from “Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation,” a set of precepts that Washington copied down for himself as a young teenager.

Henry’s Freedom Box: A True Story from the Underground Railroad by Ellen Levine: Enslaved Henry Brown grows up not knowing the date of his birth and longing to be free. Forcibly separated from his family, Henry eventually decides to mail himself in a crate to the North in order to finally be free, ultimately choosing his first day of freedom as his true birthday. This true story by an award-winning author brings home the tragedy and triumph of one enslaved American.

How Children Lived: A First Book of History by Chris and Melanie Rice: This beautifully illustrated book allows young readers to compare their lives to those of sixteen children from wide-ranging periods of history and parts of the world. With photos of actual artifacts—ranging from a Viking girl’s ice skates to the helmet that a samurai in training aspires to wear—the book investigates the lives of an American drugstore owner’s son in the 1920s, an ancient Egyptian scribe in training, a Moghul Indian boy whose father raises elephants, a Dakota girl living on the Great Plains, a girl at home in industrial Britain, and many more.

I Am Human: A Book of Empathy by Susan Verde: This charming picture book celebrates the joys of being human—the curiosity, dreams, playfulness, and wonder—and gently acknowledges the challenges—hurting other people, being hurt, and feeling sad—while praising our ability to move forward to connect to other people with kindness, forgiveness, and compassion.

If You Lived When There Was Slavery in America by Anne Kamma: This seminal book—part of a history series—helps answer questions that young students have about the tragic institution of slavery, such as: Where did enslaved people come from? What were their homes like? What types of work did they have to do? Introducing this difficult topic to young readers, the book provides an age-appropriate overview of what life was like for the millions of people who suffered as slaves in America from the 1600s until 1865.

Light in the Darkness: A Story About How Slaves Learned in Secret by Lesa Cline-Ransome: Rosa and her mama sneak off at night to attend a secret school for slaves, where Rosa determinedly works on her letters and excitedly anticipates learning how to read. Along the way, she learns how important it is to keep the school a secret from the man who owns them, because he will punish them if he finds out.

The Other Side by Jacqueline Woodson: Clover, a young, African American girl, is perplexed about why a fence separates the white and black sides of town. When Annie, a white girl, starts sitting on the fence, Clover becomes brave enough to befriend her.

Elementary (Grades 4 and Up) Chapter Books

Amina’s Voice by Henna Kahn: Amina is a Pakistani American, Muslim girl in middle school, confused about how to fit in while also being true to the culture of her family. Her best friend, Sajin, contemplates changing her name to one that is more “American,” and Amina wonders if she should do the same. Her local mosque is vandalized, a heart-wrenching event. However, Amina learns to use her voice to help bring her diverse community together.

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson: This National Book Award-winning collection of emotionally evocative poems is Woodson’s exploration of growing up in the 1960s and 1970s as an African American girl. Her poems, which are accessible, powerful, and poignant, focus on the Civil Rights movement, the lingering effects of Jim Crow, personal family stories from time spent in both South Carolina and New York, and special challenges Woodson faced in learning how to read.

Harbor Me by Jacqueline Woodson: Six kids start meeting with each other on a weekly basis to share stories, challenges, and fears. Their ARTT room—A Room to Talk—becomes a safe space to chat about a parent’s deportation, a father’s incarceration, fears of being profiled, and family struggles. This uplifting novel, focusing on the concerns of these six students as they approach adolescence, conveys the idea that a shared community can make you braver and better able to face the challenges ahead.

One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia: In this humorous, Newbury Honor novel, three African American sisters—Delphine, Vendetta, and Fern—travel to Oakland in 1968 to spend time with their mother, who had previously left them behind in Brooklyn, deserting them for a new life in California. Once Cecile reunites with her daughters, she decides to send them to a summer day camp managed by the Black Panthers. Their resulting crazy summer teaches them a lot about who they are, their family, and even their country.

Return to Sender by Julia Alvarez: Tyler’s Vermont farm family has to hire migrant workers when his father is hurt in a tractor accident. Mari and her family live in constant dread that they may be deported back to Mexico, although she is both proud of her cultural background and interested in her life in America. Alvarez’s touching novel explores the friendship that develops between Tyler and Mari, despite their differences and the very real challenges they face.

The Turtle of Oman by Naomi Nye: Aref loves his life and home in Muscat, Oman, and stubbornly refuses to prepare himself for his family’s upcoming move to Ann Arbor, Michigan. Worried about him, Aref’s mother asks his beloved grandfather, Sidi, for help. Sidi takes Aref on some special adventures—sleeping on Sidi’s roof, visiting a camp in the desert, fishing in the gulf of Oman, and viewing sea turtles in a nature reserve—reassuring Aref that his time in America will be another adventure that will end in his returning home.

They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems by David Bowles: Güero, the Mexican American protagonist of this novel-in-poems, is a bookish border kid who wishes he could trade his fair skin and red hair for the darker complexion that would more clearly identify him as Mexican American. Through a variety of poetic forms, ranging from sonnets to raps, Güero provides a lively, funny portrait of the life and culture of a border kid and the challenges of seventh grade.

Teacher Resources

This is Our Constitution by Khizr Khan: Gold Star father Khizr Khan—who emigrated with his wife from Pakistan in 1980 to the United States, where they eventually became U.S. citizens, and whose son gave his life, stopping a suicide attack in Iraq—reflects on the U.S. Constitution, how he feels connected to it, and the document’s history, with a detailed explanation of what the Constitution means. Khan also examines the Bill of Rights and key Supreme Court decisions, and provides complete texts of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

Words That Built a Nation: Voices of Democracy That Have Shaped America’s History by Marilyn Miller, Ellen Sordato, and Dan Tucker: This much-hailed collection of the most seminal documents in U.S. history, aimed at upper elementary and early middle school students, includes the documents themselves, as well as brief biographies of the people who wrote them and responses to them. The book opens with the Mayflower Compact and includes the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution, key amendments to the Bill of Rights, historic speeches, pivotal Supreme Court decisions, and much more.

This Grade 4 unit, based on the award winning memoir Brown Girl Dreaming by author Jacqueline Woodson, includes instruction and materials for fifteen 90 minute lessons. In this book, the author describes in emotionally charged and evocative language her life as an African American girl growing up in the South, and in New York City, in the 1960s and 1970s. This book is available for purchase from bookstores and online vendors.

This Grade 4 unit, based on the award winning memoir Brown Girl Dreaming by author Jacqueline Woodson, includes instruction and materials for fifteen 90 minute lessons. In this book, the author describes in emotionally charged and evocative language her life as an African American girl growing up in the South, and in New York City, in the 1960s and 1970s. This book is available for purchase from bookstores and online vendors.

Tell students that you are going to pretend that you have a special machine so that you can all travel back in time to visit ancient Greece. Ask students to close their eyes and make sure that they are “buckled in,” so that they can travel back in time. Count backward, saying, “3 . . . 2 . . . 1 . . . Back to ancient Greece!” and then ask students to open their eyes.

Tell students that you are going to pretend that you have a special machine so that you can all travel back in time to visit ancient Greece. Ask students to close their eyes and make sure that they are “buckled in,” so that they can travel back in time. Count backward, saying, “3 . . . 2 . . . 1 . . . Back to ancient Greece!” and then ask students to open their eyes.

How did George Washington’s leadership at Valley Forge, and his later insistence that he serve only two terms as president, reflect his virtuous character? What did Ida B. Wells’s fight against Jim Crow laws and lynching say about an individual’s moral duty in America? Why did Padre Miguel Hidalgo y Castillo decide to break the law to help the indigenous people in his Mexican village, and what did his role as a revolutionary demonstrate about his values? Such stories of historical leaders and reformers are central to the

How did George Washington’s leadership at Valley Forge, and his later insistence that he serve only two terms as president, reflect his virtuous character? What did Ida B. Wells’s fight against Jim Crow laws and lynching say about an individual’s moral duty in America? Why did Padre Miguel Hidalgo y Castillo decide to break the law to help the indigenous people in his Mexican village, and what did his role as a revolutionary demonstrate about his values? Such stories of historical leaders and reformers are central to the  The Civic Character Formation Project (CCFP) draws on CKHG content to help students develop their own sense of character. The Character Formation Project is a nonprofit that strives to prepare students to lead fulfilling and virtuous lives. Like Core Knowledge, CCFP uses outside subject matter experts to review their material. Designed to align with CKHG, CCFP’s vividly written accounts effectively place the student at moments of moral decision making, allowing for reflection, discussion and the examination of virtue. CCFP programming focuses on seven virtues that have been exhibited throughout time by countless individuals who have worked to advance human freedom. The seven virtues are justice, respect, responsibility, integrity, self-sacrifice, diligence, and courage.

The Civic Character Formation Project (CCFP) draws on CKHG content to help students develop their own sense of character. The Character Formation Project is a nonprofit that strives to prepare students to lead fulfilling and virtuous lives. Like Core Knowledge, CCFP uses outside subject matter experts to review their material. Designed to align with CKHG, CCFP’s vividly written accounts effectively place the student at moments of moral decision making, allowing for reflection, discussion and the examination of virtue. CCFP programming focuses on seven virtues that have been exhibited throughout time by countless individuals who have worked to advance human freedom. The seven virtues are justice, respect, responsibility, integrity, self-sacrifice, diligence, and courage. Twenty-three years ago, Mary Beth Klee designed

Twenty-three years ago, Mary Beth Klee designed  Parents, says Greg, “basically understood Core Knowledge from the beginning, and we’ve stuck with it because we’ve had so much success with it”—success borne out by the school’s state test scores, consistently among the highest across Delaware’s schools, as well as two

Parents, says Greg, “basically understood Core Knowledge from the beginning, and we’ve stuck with it because we’ve had so much success with it”—success borne out by the school’s state test scores, consistently among the highest across Delaware’s schools, as well as two