“I am in the medical field and while I ‘hated’ learning anatomy, I am not sure you would want me to treat you unless I had it memorized,” writes LSC from Seattle. That’s just one of the hundreds of comments in response to a terrific op-ed by Natalie Wexler in the New York Times.

Wexler begins by addressing a growing blame-the-tests myth:

Standardized tests are commonly blamed for narrowing the school curriculum to reading and math. That’s one reason Congress is considering changes in the law that could lead states to put less emphasis on test scores. But even if we abolished standardized tests tomorrow, a majority of elementary schools would continue to pay scant attention to subjects like history and science.

Consider this: In 1977, 25 years before No Child Left Behind ushered in the era of high-stakes testing, elementary school teachers spent only about 50 minutes a day on science and social studies combined. True, in 2012, they spent even less time on those subjects — but only by about 10 minutes.

The root cause of today’s narrow elementary curriculum isn’t testing, although that has exacerbated the trend. It’s a longstanding pedagogical notion that the best way to teach kids reading comprehension is by giving them skills — strategies like “finding the main idea” — rather than instilling knowledge about things like the Civil War or human biology.

While I found the supportive comments by professionals in medicine, higher education, and other fields heartening, what really grabbed me were the comments from teachers. The vast majority see the futility of trying to cultivate skills with “a book about zebras one day and a story about wizards the next,” as Wexler writes—and they’re hungry for a more balanced, substantive approach.

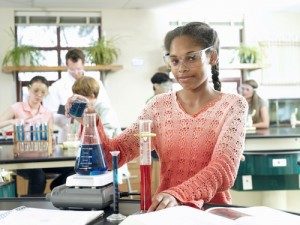

Wexler’s article generated over 200 online comments, most of which showed strong support for teaching skills as a facet of teaching essential academic knowledge (image courtesy of Shutterstock).

Here are some of the comments that jumped out:

You see this in much science teaching, too, where a great deal of time is spent on “the scientific method” – a simplified version, and often taught in a rote manner with mantras of “hypothesis, experiment, conclusion” — but little time is spent mastering the great systematic body of knowledge about how the material world works. Geology — evolution of our earth, recognizing different types of rocks, reading the landscape. Biology — a basic knowledge of the different categories and types of living things, evolution, anatomy, genetics. I could go on — but the point is, knowing how the world works, in and of itself, is important. Ignorance can lead to disaster, as voters and as individuals.

Yes, teach us HOW we learn — but also teach us WHAT we’ve learned, and what we still don’t know. Otherwise, it’s like teaching us how to use a knife and fork — but never putting any real food on the plate.

— Kathy Wendorff, Wisconsin

Thank you! This might be the best column about education that I have ever read in the NY Times. As a public school teacher for almost 15 years, it is obvious that knowledge is the key ingredient. In theory, the Common Core places greater importance on knowledge- which is good. Unfortunately, everything else that most teachers, students, and parents encounter sends a very different message. In NYS, the state tests, teacher evaluation rubrics, and talking points of school administrators (as well as politicians and most media reports- including those in the Times) almost always emphasize the need for skills (especially so-called “21st Century skills”) and downplay, or even openly belittle knowledge as outdated, boring facts that require “rote memorization”. As a liberal who believes that improving educational achievement for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds is one of the most important issues facing our nation, I am truly thankful for this column which will hopefully help chip away at the skills over knowledge myth that prevents us from really making progress in achieving better education for all.

—J. Adams, Upstate NY

I was at a staff meeting about 5 years ago when the English K-12 Coordinator pronounced: “Facts are dead. There’s NO reason to learn facts.” At another curriculum planning session … another supervisor peered over my shoulder as I was typing & said, “Why do they need to learn Shakespeare anyway?” … This may surprise ‘reformers,’ but many teachers have been teaching based on their own expertise, despite all the mindless manic ‘solutions.’ I teach Shakespeare & facts no matter what. And main idea too.

—dcl, New Jersey

As a teacher who has been struggling to teach abstract concepts like “Find the Main Idea” to fourth graders, I really appreciate this essay…. Standard reading textbooks, as the article points out, flit from one unrelated subject to another, and for many children, it all feels like so many abstract and irrelevant exercises. A thoughtfully crafted sequence of readings on a related theme of interest to children would not only give students a mastery over a body of knowledge, but also make learning skills like “find the main idea” much more relevant and meaningful.

—Ann, Kempton, PA

As a teacher of 5 years, I was told to only teach skills and was reprimanded for not doing so. This is a bigger conversation that needs to enlighten how entire districts and states see curriculum.

—Samantha, DC

Yes, the problem is that no amount of skill based learning can replace content and background information…. Students need historical and cultural knowledge (actual content) to be able to fully understand what they are reading. How can they get “the main idea” if they don’t understand what the ideas are in the first place because they don’t know the meaning of words or the allusion to a particular mythical or historical event? Content must come first! As a teacher with over 30 years of experience, I am amused by the many “innovative” skills and methodologies: KWL chars, TPCAST, SOAPSTONE, Essential questions and more “exciting” ways of teaching and learning, yet what good are these if you don’t know what you’re reading, writing, and speaking about?

—Sara, Cincinnati

As a teacher in Florida, I can verify the accuracy of this. My students spend two whole months taking tests in a school year of 180 days. There are huge gaps in their content knowledge — and they have no context for the little knowledge they do have.

—L Owen, Florida

It cheered me to read this article. Next week, I head back to school to work with a faculty which is half vehemently against the Core, half more or less just going with the flow. A 3rd grade teacher last May was heard by anyone with ears to hear that “those tests are so unfair! I never taught my kids ANY of that stuff that was on that test!” Well, unwittingly, she hit the nail on the head. She didn’t teach knowledge: she is a skills enthusiast.

— Emmett Hoops, Saranac Lake, NY

Personalized pacing (with safeguards) and personalized content are very different things (image courtesy of

Personalized pacing (with safeguards) and personalized content are very different things (image courtesy of