One of my favorite blogs is by Katie Ashford, the director of inclusion at Michaela Community School in London (where another favorite blogger, Joe Kirby, is head of English). Ashford believes all children are capable of tackling rigorous content, and she mixes a strong research base with practical advice. In a recent post, she does the unthinkable: she defends rote memorization.

As much as I disliked memorizing in school, now I’m glad I put in the effort. Math facts, historical dates, poems, quotes—these things rattling around in my head actually make my day-to-day life easier and more interesting. But in talking about education, I rarely admit that I value memorization. I fear feeding those who wrongly assume that the Core Knowledge Sequence really is a list of facts to be memorized, rather than a scaffold for building a rich, engaging curriculum.

So I’m delighted to see Ashford making the case, and Michaela’s students proving the point:

Although I’ve always believed that a knowledge-rich curriculum could lead to great things, I had never seen it in action until I came to work at this school….

Not only do pupils genuinely enjoy knowing loads of stuff, … rote learning has proved to be incredibly useful when they come across new knowledge. They are able to make connections and inferences that someone who lacks such knowledge would simply not be able to make.

Here is one of my favourite examples of this:

I was reading through a biography of Percy Shelley with … one of my year 7 classes and my tutor group. Many of the pupils in this class have reading ages far below their chronological age. More than half the class have Special Educational Needs….

In the biography, we came across this piece of information:

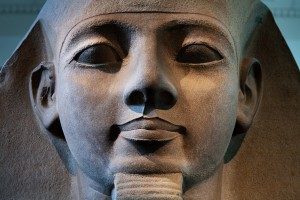

“Shelley began writing his poem in 1817, soon after the announcement that the British Museum was to acquire a large fragment of a 13BC statue of Rameses II from Egypt.”

I explained that Rameses II was a powerful Egyptian Pharaoh.

Within seconds, a forest of hands shot up. Slightly baffled, I asked one of the pupils to tell me what was wrong.

“Miss, how could Rameses II be a Pharaoh in 13BC when Egyptian civilisation ended in 31BC? Miss, that doesn’t make sense.”

I was stumped and couldn’t answer for this. It later transpired that there had been a typo in the printed version of the biography. Instead of 13BC, the date should have said 1213BC. Because I lacked knowledge of the date of the end of Egyptian civilisation (which the pupils had learned in Mr Porter’s History lesson), I would never have been able to spot the mistake. In fact, I would have had a completely incorrect understanding of Rameses II and the statue, which was over a thousand years older than I had believed it was….

My pupils, by contrast, had been empowered by their knowledge. Consequently, they were in a far stronger position to critically analyse the text they had been given than I was.

Rote learning is perceived to be a dull, mindless activity that leads to little other than parrot-like recall, but this simply is not the case. On the contrary, mastering lists of important dates is essential for critical thinking to take place.

Ramses II, in the British Museum, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Ramses II, in the British Museum, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.