By Debbie Reynolds

Debbie Reynolds has been teaching for over ten years in grades K-2; she currently teaches second grade at Diedrichsen Elementary School in Sparks, Nevada. Diedrichsen is located in a middle- to lower-socioeconomic neighborhood, with 44% of students being of low-SES background. The student exemplars presented in this article are from a student that is in the lower 30% of Reynolds’s class. All of her students, except two special education students, are able to accomplish these writing tasks with very similar outcomes.

Not long ago, I dreaded my second grade students’ writing. I agonized over helping them have something meaningful to say, elaborating on their ideas, and adding information and details. Despite my best efforts, their writings were often flat, repetitive, and rigid.

Today, I truly look forward to my students’ writing activities—especially their final products.

Here are three excerpts from a recent assignment in which my students wrote as if they were participants in early America’s Westward Expansion:

My family and I are heading to San Francisco. I am getting there on the Oregon Trail in a wagon. I am going so I can mine some gold and have a better life.

We faced many hardships on our journey. We sometimes broke a wheel going across the dirt. We faced the cold at night. We faced the heat in the desert. We faced danger in the Snake River. We faced ruts in the dirt on the trail.

We felt tired from the long trip and can’t wait to meet new people.

My students’ writing changed when I began teaching Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA). At first, I did not see the potential for their writing, but as I tried different strategies and organizational tools, their writing transformed, becoming reflective and thorough. When students are given an opportunity to build knowledge and a way to organize what they’ve learned, their writing thrives. They are motivated to share their newly formed thoughts and ideas. Having taught second grade for six years, I’ve found some of their finished projects quite amazing.

In my class, we use a four-step process to produce great writing:

1. Build Background Knowledge. First, I begin our writing projects by building my students’ knowledge and vocabulary through listening to and discussing CKLA’s read-alouds. The read-alouds are grouped by topic; each topic takes two to three weeks and has ten or so read-alouds. My students have learned about fascinating domains like Greek Myths, Cycles in Nature, and Immigration. At the conclusion of each read-aloud, my students answer comprehension questions and discuss key details from the story with their peers, as CKLA suggests. We use this time to clarify misconceptions and deepen understanding. Listening and speaking about the content really helps them gain knowledge and grasp concepts.

2. Transition Oral to Written: Students then participate in some sort of writing exercise, such as whole group or individual brainstorming to list key ideas and details, individual or group note-taking, summarizing, or illustrating a scene or idea—anything that helps them take the content they’ve heard and write it out. This helps them solidify their understanding. We do this with almost every read-aloud. Sometimes it’s independent, sometimes it’s in small cooperative groups, and sometimes it’s whole group.

3. Organize Information: Once we finished all or most of the read-alouds for a given topic, I provide my students with a graphic organizer to help them organize and build their writing piece. Throughout CKLA’s domains, we use a variety of different forms of writing such as narrative, informational, argumentative/opinion, reflective, or a friendly letter.

4. Publish: Once the graphic organized is filled out, they begin a rough draft. What they bring to each part of their story is truly amazing and individualized. Although you will see some of the same ideas, no two stories are alike. They each carry their own voice and their own selection of details. After completing a draft, they edit their writing independently for mechanics and grammar, and have a peer edit it for a second time. After self-editing and peer-editing is complete, I conference with them individually to offer ideas for revisions and sometimes further editing. At long last, they rewrite their rough draft into a final copy and finish with an illustration.

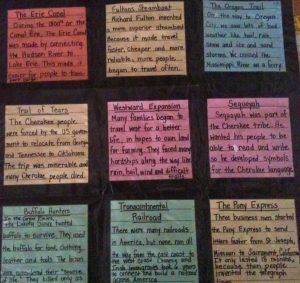

For the domain on Westward Expansion, which has nine read-alouds, I chose to use the CKLA activity of creating quilt squares and ultimately a final quilt. This engaged the students in writing every day about key ideas. After each read-aloud, I began by having them brainstorm a list of key ideas and details from the read-aloud. Then they filled in their individual quilt square template (which is provided in the CKLA Westward Expansion Anthology’s workbook pages).

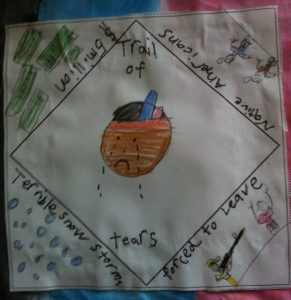

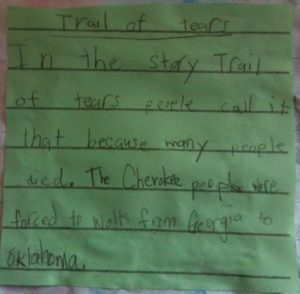

Here’s a sample from one of my students. The front of the quilt square has key details and phrases, as well as an illustration of the story. The back of the quilt square has a summary of the story’s main ideas and details. Once they are assembled, student’s individual quilt squares help them create a writing piece that conceptualizes their leaning.

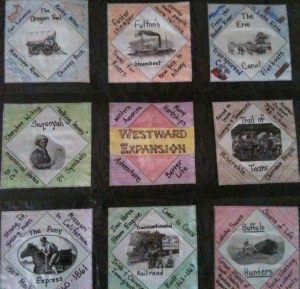

Here is the final quilt that I made alongside my students. (It’s much easier to read because I did mine in black ink instead of pencil.) As they completed their squares, I did the same. We enjoyed sharing our pieces as we completed them. Once all squares were completed, I put my quilt together as an example for them to follow. We glued them onto a 24” X 24” colored piece of chart paper, and we talked about making a 3 X 3 array on each side being careful to line up the right fronts and backs.

For this particular domain on Westward Expansion, I chose to have them write a narrative piece about traveling west with their families and what they may encounter on their journey. The graphic organizer I used, shown below, breaks down each part of their story into smaller pieces, so that students are not overwhelmed by the breadth of the information they need to cover or hindered in trying to organize all of it. I give my students one prompt and topic sentence a day to work on from “sloppy copy” to final copy. The activity takes about 30-45 minutes a day as I have them use their new knowledge (and often background knowledge developed in prior domains) to develop each part of the story. Since they’ve also been writing and summarizing information every day on the same topic, they have a nice repertoire of information to pull from.

Voilà! A beautiful and meaningful masterpiece…written by a second grader!